David Barker’s Reflection after Five Papers is a catalog of unanswered questions. Over 2022–2024 he published five critiques of influential studies claiming that higher temperatures reduce economic growth, invited responses from the original authors, and despite publicity of his work received none. I found this article to be critical and almost comical in the way that Barker points out aspects of studies that he perceives as lacking. Barker emphasizes that his critiques were not obscure: his Econ Journal Watch comments have been widely downloaded, he wrote op-eds in major outlets, and he even testified before the U.S. Senate Budget Committee; yet the authors he critiqued did not reply to his open invitation to engage.

Barker opens by reminding readers why the issue matters. If temperature changes only reduce the level of GDP, the economic consequences look modest compared with long-run growth; for example, he cites William Nordhaus’s estimate that a six-degree-Fahrenheit rise reduces year-2100 GDP by about 2.6 percent—small relative to the compound growth that could make the world about “five times higher” than it is now by 2100.

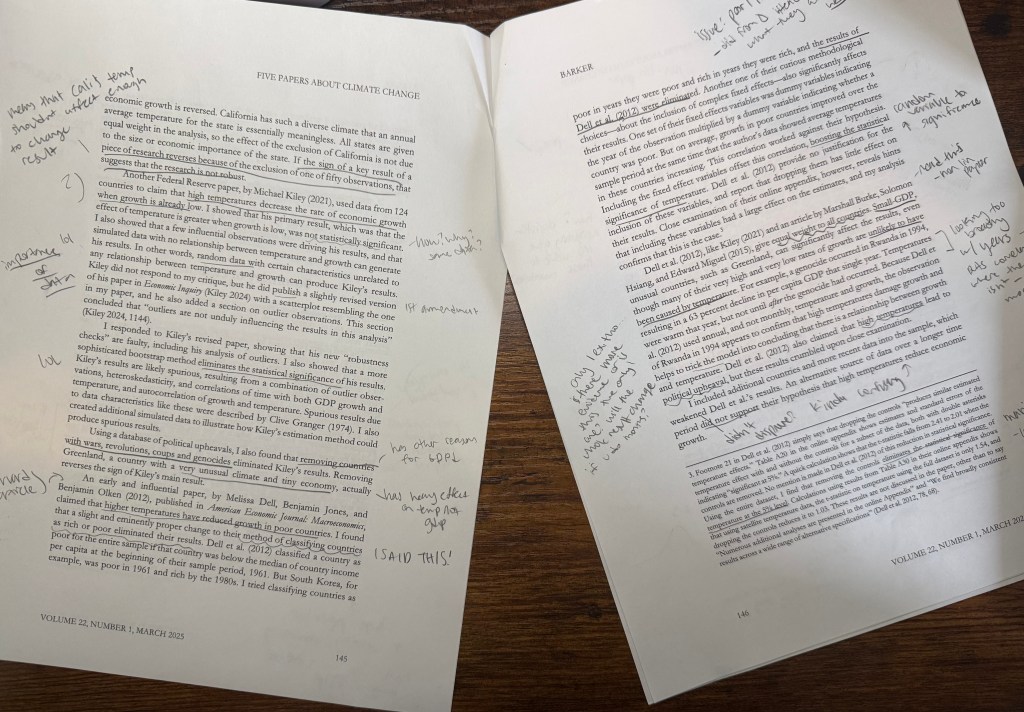

Across his five comments, Barker shows concrete methodological issues that inflate the claimed growth effects. He recounts, for example, that Dell, Jones, and Olken’s classification of countries as “poor” or “rich” based on their 1961 income is a choice that, when changed to a time-varying classification, eliminates the original paper’s result. What I found interesting here is that while reading this paper, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, I also questioned how the classification of poor vs rich affected the results. Specifically, this showed me that it is important to view studies with a critical eye, so you can attempt to see all sides of the research. He also flags how Burke, Hsiang, and Miguel’s widely cited Nature paper gives “equal weight to all countries” which allows some countries to significantly skew the results because they have alternative reasons for having extreme growth rates. Barker then cites an example from Rwanda to back up his explanation. Yet here is where I questioned the critiquer, and wondered if there is more evidence of highly skewing country data or if there are only a couple– and if they cancel each other out regardless.

The idea behind Barker’s reflection is not only these methodological corrections but the pattern of silence that followed their publication. He observes that honest mistakes are typically random in sign and size; yet, he writes, many of the errors he documents tend to bias results in the same direction—toward stronger claims that warming will slow growth a lot—and the lack of authorial engagement prevents those claims from being tested and corrected in public. He invites the original authors to debate and to test conflicting ideas, and he asks readers to treat non-response as relevant evidence about the reliability of some results.

Barker’s conclusion is a call for greater transparency and engagement: if policy choices of immense magnitude rest on findings that cannot survive straightforward robustness checks or that go unanswered when challenged, then scholars and policymakers should be more cautious about treating those findings as settled. This article does not, nor do I, deny that climate change poses risks nor that some catastrophic thresholds might exist, but he argues that policy should be informed by reproducible, well-reported evidence, especially when trillions of dollars and generational outcomes are at stake. Whether one accepts all of Barker’s corrections, his paper is a reminder that reliant, open data, are key to confident and accurate policy guidance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.